Image from No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School at McDonald Manitoba, courtesy of the Walter Powell Collection, who attended at the same time as Jim McPhee. To view other images of #3 B&G School, click here. To see the list of graduates, click here.

Being "washed out,” (as it was called,) was very disappointing; but I wished to carry on flying; and requested a remuster, to air gunner training. After a few days back at Brandon Manning depot, I was posted to Bombing and Gunnery school #3 at McDonald, Manitoba. It was now Christmas time, and I was eligible for a short furlough. As the distance to home in Ophir, Ont. was too far for the few days that I had, I decided to accept an invitation to spend the holiday with my relatives in Fort William (now a part of Thunder Bay). My mother's sister, my Aunt Mary McNally, and her husband treated me like one of their own. Aunt Mary was very much like my mother, and when I awoke in the morning and heard her talking on the phone, I thought for a moment that I was at home. The McNally’s lived on a farm in a little place just west of Thunder Bay, called Murillo. I had four McNally cousins, Betty, Ida, and twin boys, Jim and Sam. Ida and I were the same age, but they were all fairly close in age, so that we had a great time together. I also visited my Uncle Tom Cooper, a half brother of my mother. His wife was Aunt Alma, and their children were daughters Marion, Edna and Norma. They had visited us on the farm in McPhee's Valley, on a couple of occasions previously, so that I knew them quite well. My Uncle Tom had been a railroad conductor on the CNR but was retired by that time. The relatives all got together during my visit, had a wonderful Christmas celebration, which made being away from home for the first time at Christmas much easier. (Little did I imagine that my next Christmas would be in a P.O.W. camp!) It was a great chance to become better acquainted with my family in the Lakehead area, since, because of the distance; we did not meet too often.

Just after New Year I reported back to McDonald to carry on with training to be an air gunner. The emphasis was on gunnery of course, including the intricacies of the .303 Browning machine gun which we had to be able to take apart and assemble in the dark. Of course, marksmanship was stressed, with skeet shooting, rifle range, and air to air drogue shooting occupying much time. Air craft recognition was also a major study, as no one wanted to fire on friendly craft. We also spent time on the basics of navigation, map reading, and continued to do the physical training, and the military drill.

|

Image from No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School at McDonald Manitoba, courtesy of the Walter Powell Collection, who attended at the same time as Jim McPhee. To view other images of #3 B&G School, click here. To see the list of graduates, click here. |

The recreation facilities on the station were first class, with equipment to do gymnasium, basket ball, indoor soccer, and a particularly vicious game called Borden Ball. (JB Note: In Canada, handball was originally called "Borden Ball" because a simplified version was introduced during WWII by European prisoners of war detained at Camp Borden, Ontario. In Saskatchewan, an equally vicious game called Murder Ball was played. Source Canada Encyclopedia and friends) Bowling alleys and a theater were available.

Two types of air craft were in use at McDonald, both obsolete operational planes, one was the Lysander, the other the Fairey Battle. The Lysander was used to tow the drogues, and the Fairey Battle carried the training air gunner. The ammunition was marked so that the drogue was stained a certain color which could then be matched with a certain shooter. A seven per cent hit rate was considered acceptable.

A Fairey Battle, image from Website lineone, Courtesy of Nigel Roling/Pentavia Digital Imaging

Portage La Prairie was the nearest town with any appreciative population, being seventeen miles from the school, so that we were not distracted by the night life there. However, there was the usual beer parlor, the only drinking establishment: Actually, because of the distance we spent most of our leisure on the base, as there were more facilities there than in town.

Winnipeg was some one hundred miles away, so that I had just one visit there, and my lasting impression was how cold it could be. The winter of 1943-44 was notable for the heavy snow throughout the country, and southern Manitoba was no exception. One winter storm lasted three days, during which it was not possible to go out except to go from building to building. Being a typical prairie blizzard, with high winds and low temperatures, snow was piled up against the northwest sides of the buildings. Snow drifts up to the full heights of the buildings covered walk ways. Following the storm the whole station personnel were required to work with shovels anywhere that snow ploughs could not access. The snow was hard packed and came away in solid blocks, which would have been great for building igloos. Gunnery training lasted eight to ten weeks.

In March 1944, I was again posted, this time to Valleyfield, Quebec, for what was called "Commando" training.

Image courtesy of Lloyd Campbell and Susan Campbell, son and daughter-in-law of C.C. Campbell Image courtesy of Lloyd Campbell and Susan Campbell, son and daughter-in-law of C.C. Campbell |

This consisted of six weeks training by the army, and I guess was supposed to toughen us up, and prepare us for the possibility of having to survive in a hostile country, in the event we were shot down and captured by the enemy, or in case our operational air field was attacked by a ground force. All of our officers and NCO's were from the army except for a few air force liaison officers. The army officers were all from previous combat experience were tough, fair and firm disciplinarians. The air force officers were non-combatants, who were caught up in protocol and the fact that they were officers. Much of the time we were in a state of incipient revolt in our dealings with these pompous persons. During our time at Valleyfield, we learned how we could endure conditions that we couldn't imagine. Being March and April, the weather, most of the time, was typical of winter and early spring. Whatever the weather, we did our thing- obstacle courses, twenty mile route marches, rough terrain exercises including wading through rivers and canals in which the ice had been broken to accommodate us. While wading through these ice sheets, gunners fired over our heads with live ammunition. We practiced bayonet drill during which in single file, we had to impale a mannequin, disengage and quickly, get out of the way of the next man, or suffer the consequence. Many of the men who had been raised in a protected environment were sure that we were going to die of exposure, but during all of our time there, no one became ill with as much as a cold. Blisters from the long marches were the most common malady, and as we toughened, even that problem disappeared. |

By the time we finished with this training we felt we were ready for anything. In spite of the rigorous activities, this was a very enjoyable experience. Certainly, I am sure that the things that we learned there greatly contributed to our survival in the bad days that were ahead. In Valleyfield we again encountered our French-Canadian fellow citizens, this time civilians. We were surprised to realize that, unlike other locations in Canada, we were not welcome in the town, except in those places where we might spend some money. The conscription issue had been boiling for most of the war, and of course conscription was totally unacceptable in Quebec. The most hostile ones were the young male Quebecois, many of them being what was then termed "zoot suitors" identified by their clothes. The fashion consisted of suit coats which had grossly padded shoulders, trousers which were baggy with tight cuffs, accented with watch chains and fobs. During our stay there we had several altercations with this element, so that we did not go into the town except in groups of four or five or even more. Eventually the town was declared out of bounds, and soon after we were out of there. From Valleyfield we were posted to Lachine "Y" depot to await assignment which was almost always to Europe, or to coastal command. We were posted overseas to Britain, which meant we were allowed a short embarkation leave, with enough time to spend a couple of days at home.

I remember being on a "high", very enthusiastic about all the places that I had seen and all the very exciting things that I had done. I was anticipating travel overseas to see what this war was all about. My parents did not share my enthusiasm. They had live through the recent war in which my uncles had participated, one lost his life, one had had a gruesome trench warfare experience, and two others had various grim experiences. They had a better appreciation than I of the real nature of war. However, they were down to earth people who knew that, under the circumstance, there was nothing that they could do to alter the situation. For the first time in my life I remember my father embracing me, having tears in his eyes, a break in his voice, and of him being emotionally on the edge of his control. My mother who was a very warm hearted, physically affectionate woman was in tears. Suddenly, the situation was not as romantic and exciting as it had been. Now that I am a parent, I cannot help but wonder how I could handle such a farewell. From that day, I have a much different image of my parents.

Back at Lachine, I awaited an overseas draft, in the meantime had a good time in Montreal. Again, we had to go to town in groups for protection, for the same reasons that we had to in Valleyfield. The resentment against conscription was directed against the volunteer military service, no doubt augmented by the reaction of the sailors, soldiers and air men to the so-called "draft-dodgers". The aggression was met with like, resulting in some very nasty incidents. Since then I have thought back to the French-Canadian volunteers in Manning depot in Toronto {the School of English] and how they were insulted by the Anglophone NCO's. One time when a couple of the French-Canadians were having a private conversation in French an NCO shouted at them,” Stop speaking that frog talk, and speak a white man's language". There were two sides to the nasty situations, and the Quebec men certainly had their dignity challenged, and unnecessarily.

Image found by Susan Campbell in Library and Archives Canada, the Ronald Inness Collection Image found by Susan Campbell in Library and Archives Canada, the Ronald Inness Collection |

In April or early May, 1944, an overseas draft included my name, with a special assignment attached. The troop ship "the Empress of Ireland", required gunners to man the anti aircraft guns for the trip across the Atlantic. Also required were spotters to watch for submarines and enemy air craft. As a result, several of us from the "Air Gunner" classification, were seconded to the ship company to fulfill those roles. We were sent as an advance party to Halifax to take on these duties and to receive some orientation and training in our duties. JB note: CP brought out new passenger liners for its Atlantic Service like the 14,000 ton "Empress of Germany" and just prior to entering service the name was changed to "Empress of Ireland" Source: wiki |

I was assigned to the bow of the ship to man a turret of oerlikon guns. The trip through the eastern part of Canada was a first to me, and I was certainly impressed with the beauty of the countryside. The rolling stock of the railroad was not luxurious, consisting of ``colonial cars", which were mostly of wooden construction, the seats being much like park benches, and like park benches had no padding. As I remember, the food was not great, being on the edge of edible, causing much grumbling. We had a choice, eat it or leave it and the military theory was that a complaining troop was not dangerous.

Shortly after arriving in Halifax, we were marched to the dock area and boarded an almost empty ship. Our sleeping quarters were well below the water line in a cabin with sixteen hammocks, with barely room to move between them. Fortunately, for the gun crews, we were able to spend many hours on duty on the deck at our stations. The gun battery that I manned was on the extreme bow of the ship, although at that position we were really bounced around in the early spring seas of the north Atlantic. Often we were apparently well below the level of the sea, alternating with an ascent several stories above; as the ship went through the crest and trough of the waves.

There was only one really tense moment when a twin engine air craft was spotted near Ireland; this was quickly identified as a Boston light bomber from coastal command. We failed to encounter any submarines which did not make us a bit unhappy!

The food on ship, served to the "other ranks", (which included us) was verging on the inedible. Our utensils consisted of a knife, fork and spoon, and two mess tins, with hinged wire handles. The tins measured about six inches by five inches by two and one-half inches. The food was placed in one of these containers and the beverages in the other. The only alternative to having all the items thrown together was to skip anything that you didn't want mixed in. Having canned plums thrown in with beef hash was not that appealing, especially when the hash had runny gravy. Most of the time it was not too difficult to pass on the whole disgusting mess, along with the upset stomach, especially when the sea was rolling.

Trying to sleep in the crowded confined quarters was a chore, as one swung back and forth [or end to end] in a hammock which frequently bumped your neighbor. Many of the men were immobilized by motion sickness, and for three days there was lots of motion as we sailed through a spring north Atlantic storm. Actually the trip was uneventful, lasting about five or six days. Early one morning we could see Ireland ahead. We skirted around it for several hours, docking at Bristol, England.

|

From Bristol we were transported to Brighton by military buses. As it was spring, May 1944, the countryside was at its best with everything garden green, and blooms in prime. With the groomed hedge rows and cultivated crops so neat, the whole scene was so peaceful; it was hard to imagine that there was a deadly war going on. Brighton, our destination is a holiday resort city on the south coast of England, with beautiful hotels, impressive homes, and lush gardens. Our billets were in one of the luxurious hotels, giving us the best accommodation that we would enjoy for a long time. Just down from our quarters was the English Channel, with wide beaches which were barricaded with concrete tank barriers and rolls of barbed wire. Not long after our arrival we experienced our first air raid, but there was no action near. A few days before we arrived, a nearby park had been strafed by a German fighter plane, killing some people who were caught in the open. We were warned to take the air raid siren seriously. By June 10 (approximately) we were on the move again, arriving at Wellesbourne, Montford, number 22, Operational Training Unit [OTU] , near Stratford-on-Avon, and about mid way between Gloucester and Cheltenham. Orientation to the Wellington Bomber training planes, intensive classes in the geography of flying space, in and around Britain occupied about ten days. |

RAF Identity card issued for Sergeant Jim McPhee upon arrival in the UK. Image courtesy of Jim McPhee

Crewing up was a self selection process, which was amazingly smooth, with compatible individuals finding each other, in almost always happy arrangements. My first contact was with the NCO personnel as we were housed together in the sergeant’s mess and living quarters. Louis Basarab was a farmer's son from High Prairie, Alberta, a very friendly bright young man. As we were both air gunners, we decided that we would fly together. We were fast friends before we met the rest of the crew as we were in separate classes in the orientation process. In the mess we had met Ken Wilson, wireless operator. Ken was a Warrant Officer, class II, and was from Eastern Ontario. When it came time to fly, we met the three commissioned officers that completed the crew except the flight engineer who joined us at the next step [Heavy Conversion Unit]. Flight Lieutenant Albert Steeves was a pilot who had spent a year in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada as an instructor at Service Flying Training School. Flying officer Al Rowley from Alberta was a navigator. Pilot Officer Lloyd Frizzell from New Brunswick was our Bomb Aimer.

F/O L.W Frizzel

|

FL A.E. Steeves |

Sgt J. A. McPhee |

F/O A.B. Rowley |

WO 1 E.K. Wilson |

Sgt. H. E. Clark |

Sgt. L. Basarab |

L to R: F/O L.W. Frizzel, Bomb Aimer |

||||||

From June 29, 1944, we trained intensively, flying nearly every day, and taking ground classes in between. Subjects such as map reading navigation, taking fixes, on landmarks, mechanics and maintenance of Browning machine guns, marksmanship in air with the principles of deflection shooting, Fighter affiliation with cine cameras, and on the ground, skeet shooting, rifle range, handling hand guns. As a crew, we practiced evasive action, with simulated attack by a fighter plane, high level bombing, night flying, many cross country flights, day and night.

On August 16, 1944, we were sent on a mission called "Diversion Bulls Eye". Our mission was to fly to the Dutch coast, hopefully to simulate the approach of a bombing attack on Germany. This was orchestrated to induce the German fighter interceptors, to take off from their bases, chase us, and deplete their supply of fuel. We were to reverse course and head back to England before the fighters had a chance to catch us. The calculations were a little off that day, the German fighters did get through, and we ended up with a hole in the skin of our aircraft. Fortunately we escaped with no one injured, and I believe no other air craft was damaged. On Aug. 18, we did a similar exercise, with no excitement whatever.

Our course finished at Wellesbourne, we moved again this time to Yorkshire, to learn the intricacies of the four engine Halifax bomber. This station was a Heavy Conversion Unit located at Wombledon, Yorkshire, and was our home for the next couple of months. It was here that we were joined by Sgt. Edgar "Nobby" Clarke, from the RAF, who completed our crew. For some reason the flight engineers were all from the RAF. Clarke was a great fellow who was easy going and easy to get along with everyone. Between our stint at Wellesbourne and Wombledon, we were given a few days off, which allowed us to go to London to explore that great city, which we did for many hours a day on foot and by the Underground.

Airforce crew at HCU (Heavy Conversion Unit) Wombledon, October 2-30th, 1944

Image courtesy of Jim McPhee. Move your cursor over the photo to see names displayed.

"Del Rowley is in front row right on the end. On the left of the first row is Lloyd Frizzell, Ab Steeves and Jim Mcphee. In the second row, from the right of the picture, the first lad I don't remember. Next to him is Louis Basarab, next is Edgar Clark and next to him is Ken Wilson."

Time has dimmed the memories, but I remember a very nice hostel, with friendly young women staff who asked us if we would like to be "knocked up", in the morning and what time. Of course, the words "knocked up" had a much different meaning to them than it did for us. Fascinated by places like Piccadilly Circus, Trafalgar Square, Nelson's monument, Parliament, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul's Cathedral, London Bridge, Tower of London, Buckingham Palace, Hyde Park, Kensington Gardens, I walked for miles. In between, we sampled the pubs and night life. Piccadilly Square was the territory of the ladies of the night; the black-out did not seem to inhibit their activities. This was a new experience for me, but fortunately my home training, and the venereal disease lectures from the medical officers, prevented any thoughts that I might have about purchasing their services.

While I was in London, the "buzz" bombs were coming over from Europe. These devices were actually unmanned air craft containing a bomb which had an automatic pilot, and were sent over London, the motor was programmed to cut out, and the device came down wherever, exploding on contact with the ground. One of these devices came down about a block away from our hostel, killing four hundred people.

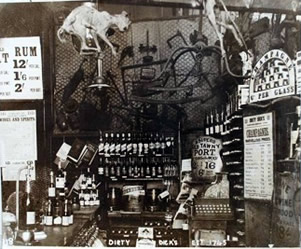

|

One pub in London impressed me. It was called "Dirty Dick's" and lived up to its name, with all kinds of clutter around, and cobwebs hanging from the ceiling timbers. (JB note: Dirty Dick's was established in 1765 and still exists today) London was crowded with service men from every corner of the Empire and the United States, as well as units of military personnel from countries in occupied Europe. |

|

Jim McPhee- My story, Page 2 continued